The elegant engineering solutions that make the robust and efficient power of the new Scania V8 possible

28 SEPTEMBER 2020

Scania’s new V8 proved to be so powerful in tests on uphill slopes that it had to be reined in. Here, some of the key project insiders recount some of the highlights from the development of the updated V8 and the new gearbox.

When Scania says it’s presenting a new vehicle or engine, the word ‘new’ is used with some qualification. After all, each product must undergo a long and arduous journey through computer calculations, component testing and field tests before finally arriving on the market.

But it always starts with innovation from the creative minds at Scania’s Research and Development in Södertälje, Sweden.

Or as the Assistant Chief Engineer Tommy Lundström puts it: “We felt inspired to reach even higher levels of customer value, by using our accumulated knowledge from other development projects.”

May 2012

In their spare time, Magnus Nilsson and a couple of other Scania R&D engineers start brainstorming ideas for a solution that would dramatically increase the efficiency of the aftertreatment system of Scania’s engines. The most important thing to understand is that the powertrain and the aftertreatment system are, together, one unit. Specifically, the more performance you can get out of the exhaust system, the more freely you can tune the engine to increase power while lowering fuel consumption. It also means that the engine can be designed more freely, focusing on simplicity and robustness. Once realised, the solution they started conceptualising would make it possible to get more emission reduction out of a limited catalyst volume. Particularly, it allowed them to run the engines at low speeds and low temperatures, while still keeping NOx emission levels low. It’s an idea that is good news for both the customer’s wallet and the environment.

The strategy for the particulate filter continues to rely on so called ‘passive’ regeneration. This means the process can take place at lower temperatures and therefore it does not consume valuable fuel. It is designed in synergy with the engine which emits low levels of soot. Again - good news for both the customer’s wallet and the environment.

“In the beginning you could say we operated under the radar of Scania’s normal processes. We were a group of creative engineers that spent a couple of long summer evenings on our ‘skunkworks’ (small group, radical innovation) project,” Nilsson recalls.

“But eventually, our idea for injecting AdBlue in two steps in the aftertreatment system got the green light from our bosses and became an important part of the new V8 project.”

This is also the background for a concept recently launched by VW – where they claim 80% reduction in NOx emissions.

The V8’s development journey in five steps

1. Digital components

Every single component in the V8 engine starts out as a model on a computer. And with the help of advanced computational models, the development team is able to quickly produce a limited number of alternatives that can be tested in real life.

2. Entering the real world

Once a component leaves the virtual world and is produced in physical form, it is subjected to load in a controlled manner until it breaks or loses its function in some way. When a component breaks, the team investigates exactly what happened and transfers this knowledge across to the computer-based model.

3. Thousands of hours in test cells

Once a component meets the design brief, it’s time for it to be tested with other components. One way to do this is in test cells, where over the course of 1,000 hours engines are exposed to stresses and changes that correspond to those they would experience throughout their working life in trucks. But the engine is also subjected to higher power and significantly higher cylinder stress than it’s built for. This allows a quicker identification of potential weak spots.

4. Testing the complete vehicle

Once an engine survives the test cells, it is put through strenuous endurance testing in a vehicle. The endurance tests involve assessing how wear and tear affects the whole design, while function testing is used to check the fuel consumption, emission levels and driveability, so that the engine delivers the intended performance.

5. Field tests by customers

Finally, there’s customer testing, in which a cross section of customers has the opportunity to contribute their views during field tests.

February 2014

In a ‘war-room’ at R&D, a tight-knit team of Scania developers has hit the wall. The team has been working on ideas for a new, automated gearbox range that would match Scania’s high output engines and the company’s philosophy of saving fuel with low revs and high torque. The team’s solution is a compact gearbox that features improved gear-changing, eight reverse gears and reduced fuel consumption, with much less internal energy loss. It’s also 60 kg lighter than before.

But now Scania’s patent office has signalled that the team’s solution touches upon an existing patent.

“For a while, our ideas were hanging by a thread,” says Per Arnelöf, one of the key hardware developers for the new gearbox. “But eventually, one late afternoon, one of our team members, Tomas Selling, had a brilliant idea: let’s decouple the gearbox from the cardan shaft and shift the range in a new way, using a planetary clutch. It was triumph through adversity; we came up with a better solution than our original idea.”

January 2016

Testing, coding, testing. In a snowy Arvidsjaur in northern Sweden, gearbox management systems developer Tomas Selling is sitting in the driver’s seat, with Peer Norberg, another key developer for the manoeuvring system, by his side. Peer has a computer in his lap, which he uses to analyse how the new gearbox behaves in a punishingly cold and snowy environment.

“The beauty of software development is that there’s almost no limit to how many prototypes we can try out,” says Selling. “Peer and I can discuss the shifting strategy that we’ve used with the designer of the hardware. We drive a few laps around the test track, do our analysis and adjust the software to try a new gear-changing tactic. Then it’s off to the test track again.”

One of the challenges with the new exhaust-treatment system was following the Scania tradition of making the best use of existing parts. “So, we had to try to move the completely new twin SCR concept into the existing muffler. It was a bit of a packaging challenge, but we managed to move into the existing ‘box’. From outside you do not see much difference compared to the old V8 muffler. But inside we have fitted more catalysts and removed some that we no longer needed. So, in the end, the new King of the road with 770 hp also follows the SCR-only strategy, avoiding costly and sensitive solutions like EGR or a VGT turbocharger,” says Magnus Nilsson, Technical Manager Emission Solution.

July 2017

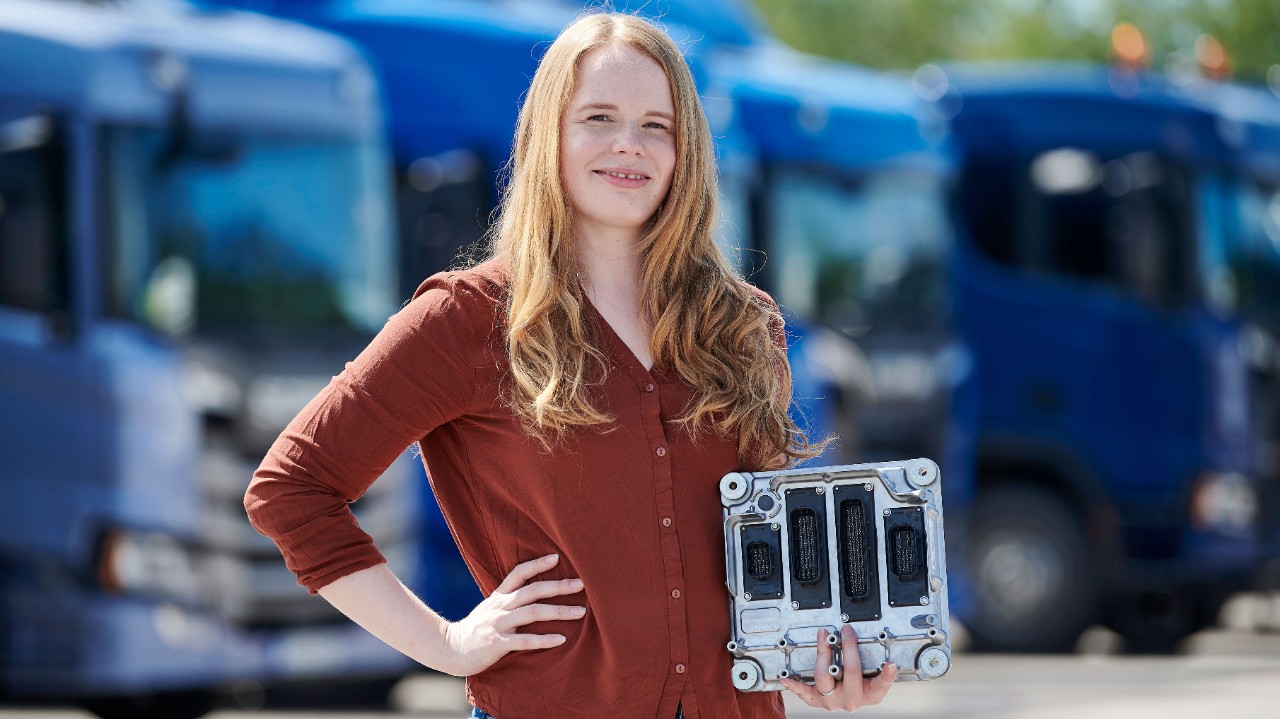

Fresh from obtaining a master’s degree in chemical engineering, Anna Andersson joins Scania’s team of software developers for the V8 update. Andersson has lived in China, experiencing smog-filled skies, and this influenced her career choice.

“I always knew I wanted to work with reducing emissions, things that make a difference for the environment. And one of the most inspiring and fun ways of doing that is to work on the ‘brain’ of the new V8,” she says, holding a box containing Scania’s engine management system for which she is writing and developing code.

“Compared to developing hardware, software development gives you instantaneous feedback. You code something, test it and see straight away if it works or not.”

May 2018

In the Sierra Nevada mountains in southern Spain, a pair of disguised Scania V8s are undergoing secret tests. They are being pushed to the limit in scorching heat. Every day, ten to twelve runs, each with 800 metres of elevation change, take their toll on both the trucks, hauling 40 tonnes, and Scania’s team.

Except for the new V8.

“In our reference slope, a constant 15-km uphill stretch, 450 hp trucks with 40-tonne loads struggle at 35 km/hour. But when we drive the same hill with the new 770, there’s a dramatic difference. It goes twice as fast, and we have to keep in the left lane to overtake all the other trucks,” says Magnus Nilsson, who is overseeing the tests on the new exhaust-treatment system.

Tommy Lundström adds, “The new 770 hp truck is actually so powerful that we have to rein it in – when we’re going uphill! We had to build a solution with an additional brake system on the 770 truck, so we could avoid it going too fast, because these are narrow roads that are 2,500 metres above sea level.”

October 2018

In one of Scania R&D’s workshops, Per Arnelöf, Peer Norberg and Tomas Selling are overseeing the assembly of a prototype for the new gearbox. Arnelöf points out a key component among the gears, parts and cog wheels: the planetary gear.

“When Tomas came up with the idea to incorporate a planetary clutch at the output shaft, it was not only a great solution for the overall performance. It also made it possible to have eight gears in reverse as we had planned from the start, which is a great advantage in certain applications such as mining and construction. This feature also makes it possible to drive in reverse with a pleasantly low engine speed for longer distances if required.”

January 2019

Anna Andersson is on location in Arvidsjaur, Sweden, to verify that everything works under what are the worst possible circumstances for the engine and the aftertreatment system: extreme cold. In this part of Lapland, temperatures often fall below minus 30 degrees Celsius. Metre-deep snow, wind, darkness and wandering reindeer also challenge Scania’s test teams.

“It was minus 26 degrees when we were there, but the engine and the new functions of the aftertreatment system behaved exactly as they should,” says Andersson.

May 2019

On one of the scheduled “Test & Drive” events for Scania’s executive management, Tommy Lundström and the company’s V8 development team manage to sneak in a 770 hp truck among the other products. The savvy management team members notice, and they are immediately impressed.

“It’s like driving the future,” one of them says.

“It drives really smoothly, and the engine sound is fantastic,” says another.

February 2020

Tommy Lundström proudly spins a 30-centimetre 3D-printed model of Scania’s updated V8 engine in his hand. It’s just a couple of months until production of the real thing will begin at the company’s engine assembly in Södertälje.

“An untrained eye might not notice the differences, but if you come close enough, you see that practically everything is different, especially the inside: the turbo, the cylinder system, the fuel pump, the control system. We’ve strived for simplicity and robustness with only the necessary parts and sensors – it’s the opposite to an ‘engineering Christmas tree’, which would make the engine expensive and difficult to maintain,” he says.

May 2020

As the launch of the updated V8 and the new gearbox nears, the team of Scania developers eagerly awaits the first reactions from the outside world: from the trade press and from customers.

The team are excited to see how people will react to a project on which they’ve spent so much of their time and effort.

“From my perspective, working with the exhaust aftertreatment system, I actually hope the customers won’t notice it at all. I just want them to experience the power, an awesome V8, the fuel savings and the great driveability,” says Magnus Nilsson.

“For me, I hope that a cyclist behind the new V8 will notice the difference of a cleaner truck,” says Anna Andersson.

“I’m really proud of what we achieved with the new gearbox. It’s light, strong and it really improves the vehicle’s fuel consumption,” says Per Arnelöf.

“The new gearbox really performs as we wanted it to,” says Peer Norberg. “It’s quiet, quick and responsive in every gearshift.”

“The new gearbox’s wider spread guarantees high torque even if the driver starts in difficult situations – customers will really feel the power,” says Tomas Sellling.

“The driving experience beats everything else. It’s exceptional for a truck. The 60 tonnes behind you feel as light as a feather,” says Tommy Lundström.